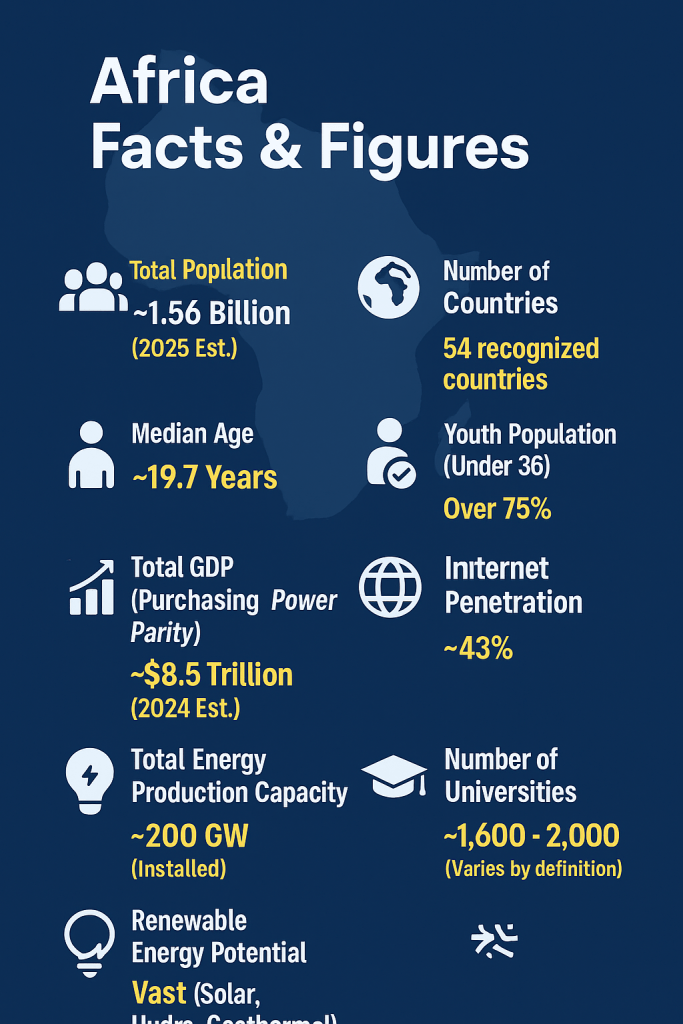

A few weeks ago, in his keynote to Kenyans, the president of Kenya admitted that building AI data centers in Kenya (as it is in many countries) is a pipe dream. This followed an agreement signed between Microsoft, The Government of Kenya and G42. He admitted that, to build an efficient data center requires about 1,000 megawatts of energy and Kenya, as a country, produces 2,300 MW. Of cause there are different demands for data centers as follows:

Small / edge site: 10–250 kW total facility power.

Enterprise / medium: 250 kW – 2 MW.

Large colocation: 2–10+ MW.

Hyperscale (Google/Amazon/MS/NVidia-style): 10 MW → 100+ MW (per site).

As the president admitted, to run one data center in Kenya, the government will have to shut down half the country’s supply in a country that is already implementing load shedding.

The Kenya AI strategy set out a very ambitious goal for Kenya 2025 – 2030. In the strategy’s budget, infrastructure set up took the cake for the highest cost when it comes to setting up an AI ecosystem in Kenya. The strategy outlines many other building blocks to AI that include data and skills. But who said Kenya must do it all, alone? A few other countries in Africa have developed their AI strategies (Egypt, Rwanda, Mauritius, Senegal, Ghana, Benin, Tunisia) and The AU has also developed a continental AI strategy.

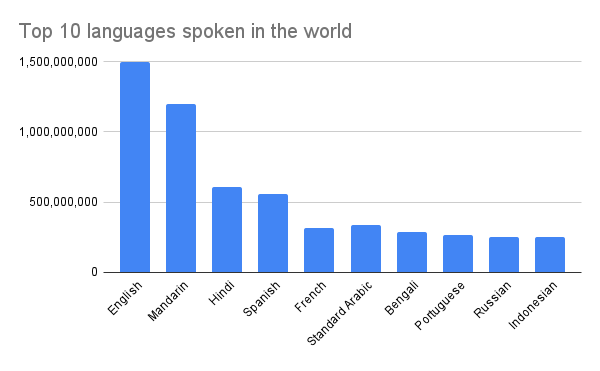

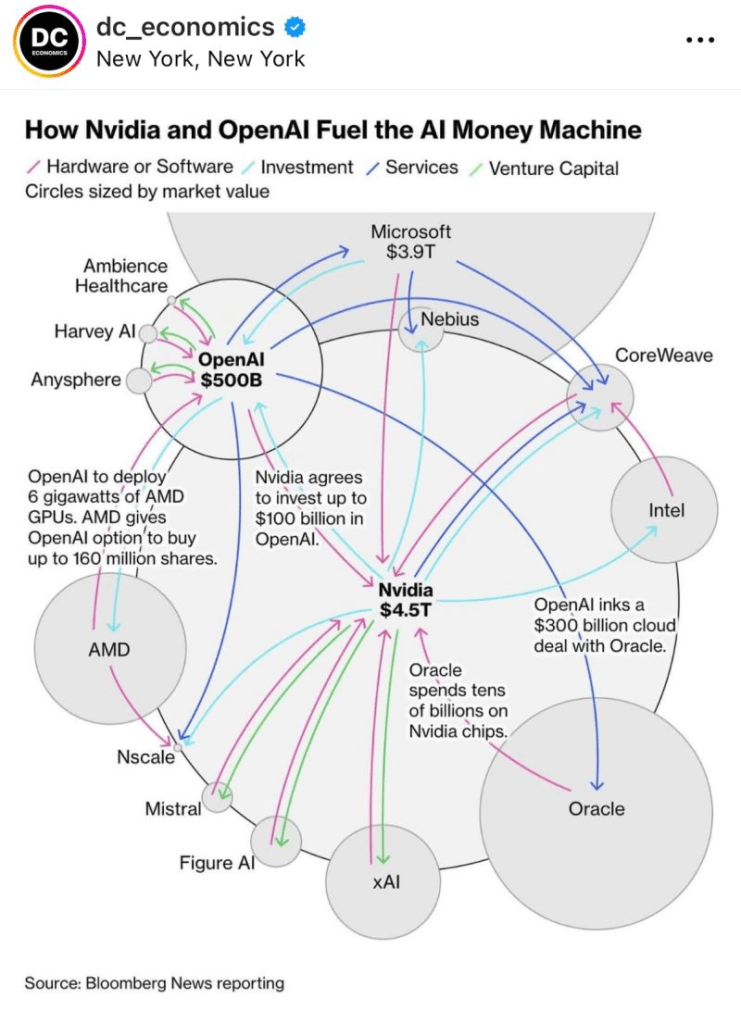

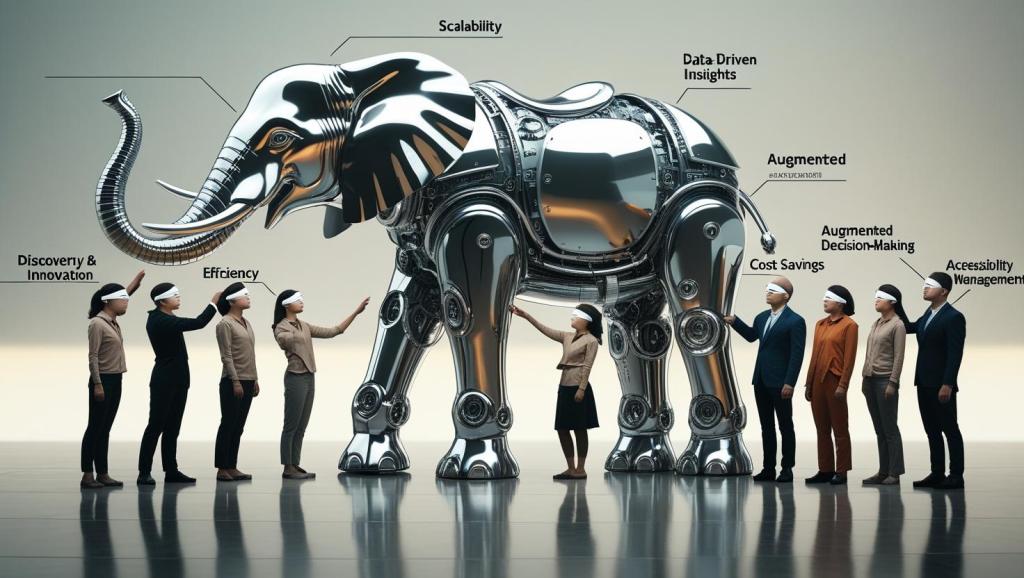

The major economies that are leaders in AI development have large populations and are also able to rely on other countries for input. None is doing it alone. Think America, China, India and those in the EU. In Africa, countries are pulling into themselves in trying to win the AI race with limited populations (demand), inputs (supply) and negotiating power (in part due to low populations) at the global stage.

In the recent past, I have come to the conclusion that for Africa to truly develop a robust AI ecosystem, the Africa Union has to take center stage. Instead of each African country trying to do everything – research, chips, data centers, cloud, regulation, and talent – the continent could unlock far more potential by specializing across regions, just like the USA has done.

In the USA model:

- California → innovation, startups, research

- Washington & Oregon → cheap hydropower + data centers

- Virginia → world’s densest internet exchange + cloud campuses

- Texas → massive energy supply + chip fabrication growth

- Washington, D.C. → policy, security, coordination

No single state tries to be the entire stack. The federated structure lets each region focus on the part they’re naturally strongest at.

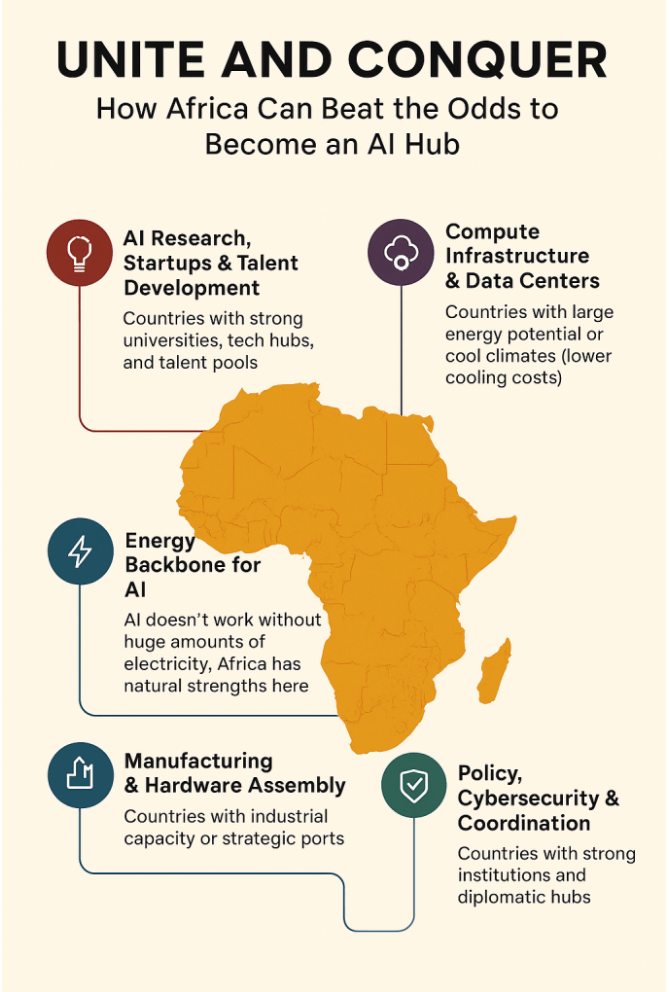

A Comparable Africa Model for AI

Africa, with a population of 1.56 billion people, can borrow from this model. The continent could distribute the AI value chain across countries according to natural advantages, energy resources, talent pools, and existing infrastructure.

1. AI Research, Startups & Talent Development

Countries with strong universities, tech hubs, and talent pools:

- Kenya → software development, applied AI, fintech, robotics

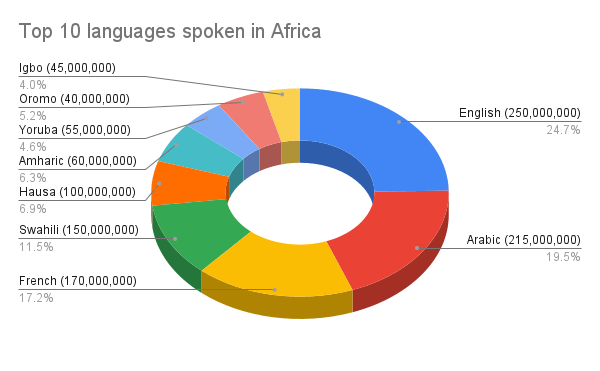

- Nigeria → large talent base, language models for African languages, AI startups

- South Africa → advanced research, university infrastructure, machine learning labs

- Egypt → engineering talent, AI for logistics and agriculture

Goal: Build models, create applications, train researchers, develop language datasets.

2. Compute Infrastructure & Data Centers

Countries with large energy potential or cool climates (lower cooling costs):

- Ethiopia → abundant hydropower for energy-hungry AI clusters

- DR Congo → huge hydroelectric capacity

- Morocco → solar + wind → green energy for GPU centers

- South Africa → existing data center ecosystem + connectivity

- Namibia → solar power + large land availability

Goal: Host large training clusters, cloud regions, continent-scale storage, green compute.

3. Energy Backbone for AI

AI doesn’t work without huge amounts of electricity. Africa has natural strengths here:

- Kenya → geothermal power

- Ethiopia → hydropower

- Morocco & Egypt → solar and wind

- Nigeria → natural gas and energy hubs

- Namibia & Botswana → massive solar corridors

Goal: Provide competitive, sustainable energy for AI training and data centers.

4. Manufacturing & Hardware Assembly

Countries with industrial capacity or strategic ports:

- Egypt → electronics assembly, chip packaging

- South Africa → component manufacturing, robotics, telecom hardware

- Morocco → automotive & electronics export hub → AI devices/edge hardware

- DR Congo → minerals supply for chip and device manufacturing

Goal: Produce servers, cooling systems, networking gear, and edge AI devices.

5. Policy, Cybersecurity & Coordination

Countries with strong institutions and diplomatic hubs:

- Rwanda → digital policy leadership

- Ghana → data governance, regional standards

- Kenya/Ethiopia → continental internet exchange points

- African Union (AU) → centralized AI regulation, ethical frameworks

Goal: Set unified standards so Africa negotiates and competes as a bloc.

Africa doesn’t need each country to build its own GPUs, energy grid, hyperscale data centers, and AI research labs. It needs a continental division of labor.

Just like the USA isn’t one state doing everything, Africa could become a powerful AI ecosystem if:

- talent clusters form where universities are strong,

- data centers go where energy is cheapest and available,

- hardware assembly goes where inputs/ports/industry already exist,

- and regulation is coordinated across the AU.

Unity doesn’t mean uniformity, it means coordinated specialization.

That’s how Africa can compete at scale in the race to AI dominance.